This Is Not a Shooting Gallery

On February 6th I spent thirteen hours on a bus for about a two-hour tour.

And I’d do it again tomorrow.

Because when you’re trying to solve something that’s killing your neighbors, you don’t get to build your opinion from headlines and vibes. You have to go look. You have to stand inside the thing people are arguing about and actually see what it is.

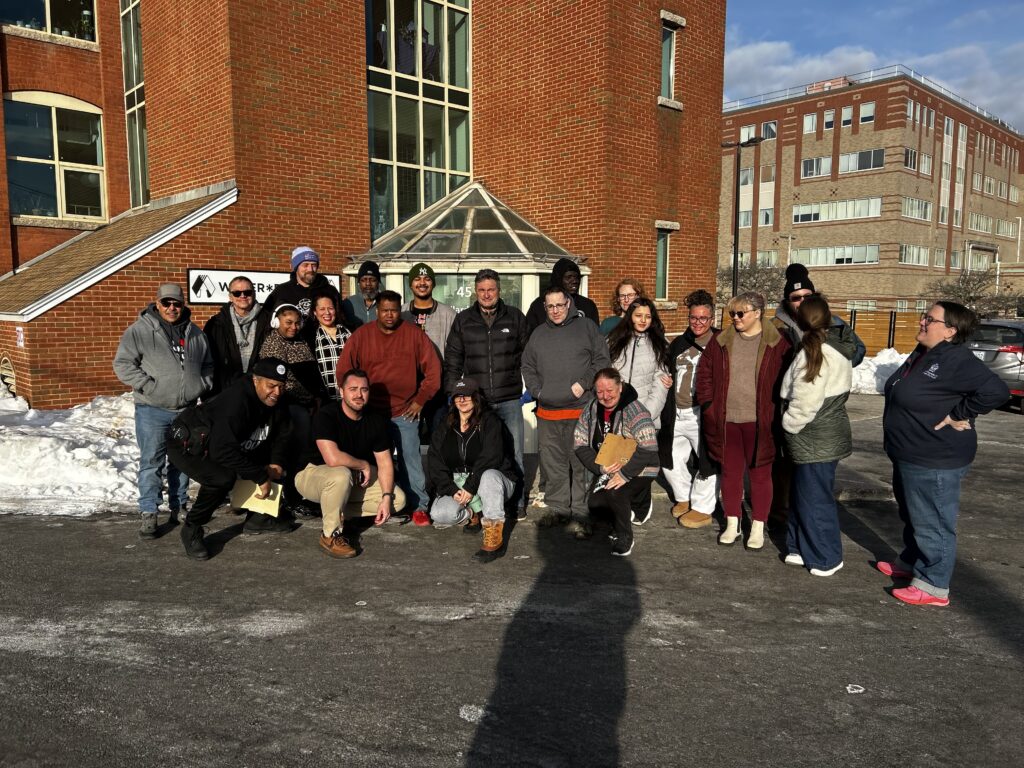

This week, a crew from Rochester toured Rhode Island’s overdose prevention center at Project Weber/RENEW.

And I need to say this plainly:

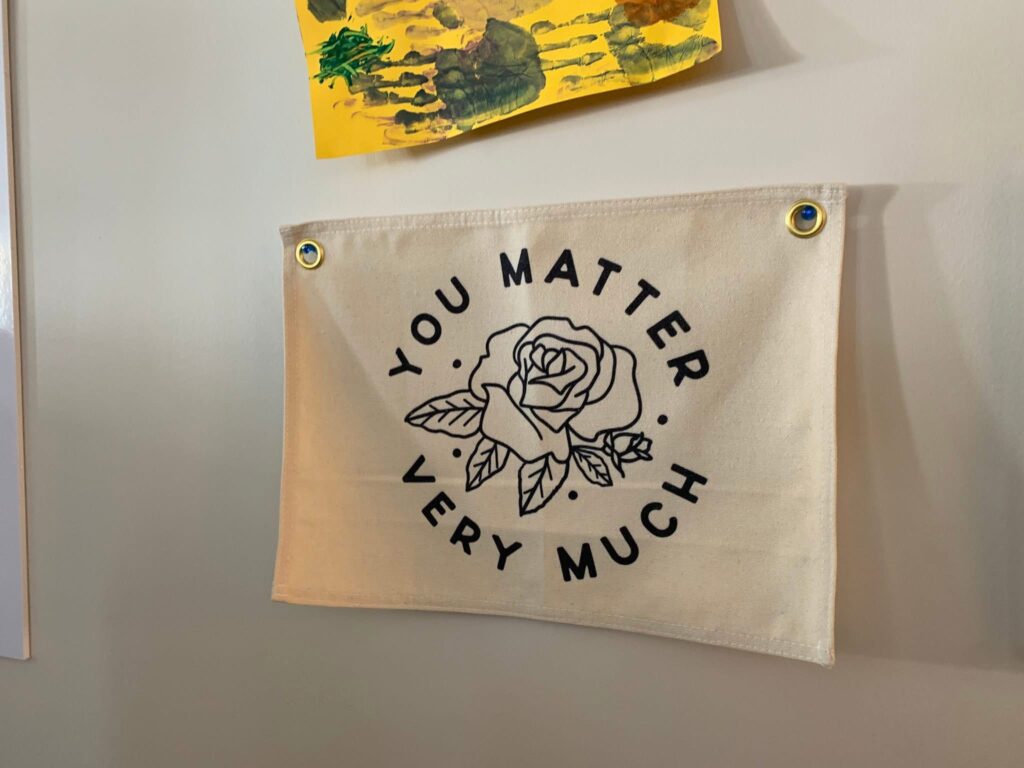

If your mental picture of an “OPC” is a dark room full of needles and despair… that picture is wrong.

Not kind of wrong. Not “well, sometimes.”

Wrong.

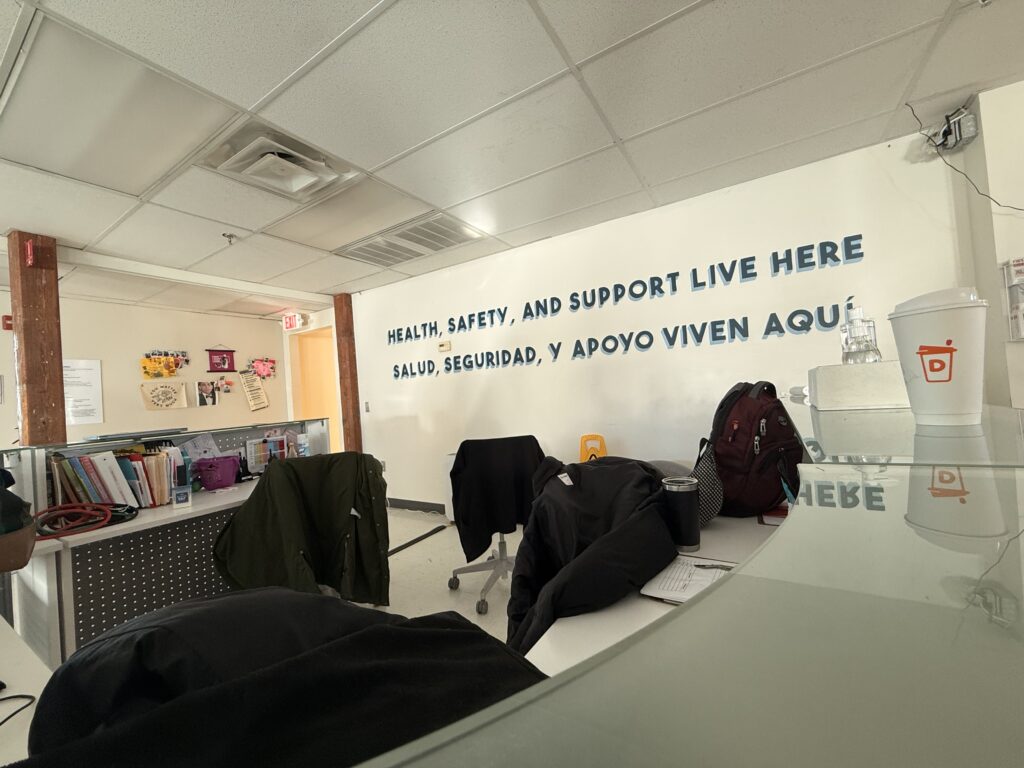

What I saw with my own eyes was the opposite of a shooting gallery.

It was a building that is service-heavy and relationship-heavy, a place that somehow manages to reach people most systems can’t reach, then builds enough trust to bring them back… and back… and back… until medical care, mental health care, and recovery support start sticking.

And here’s the part I can’t stop thinking about:

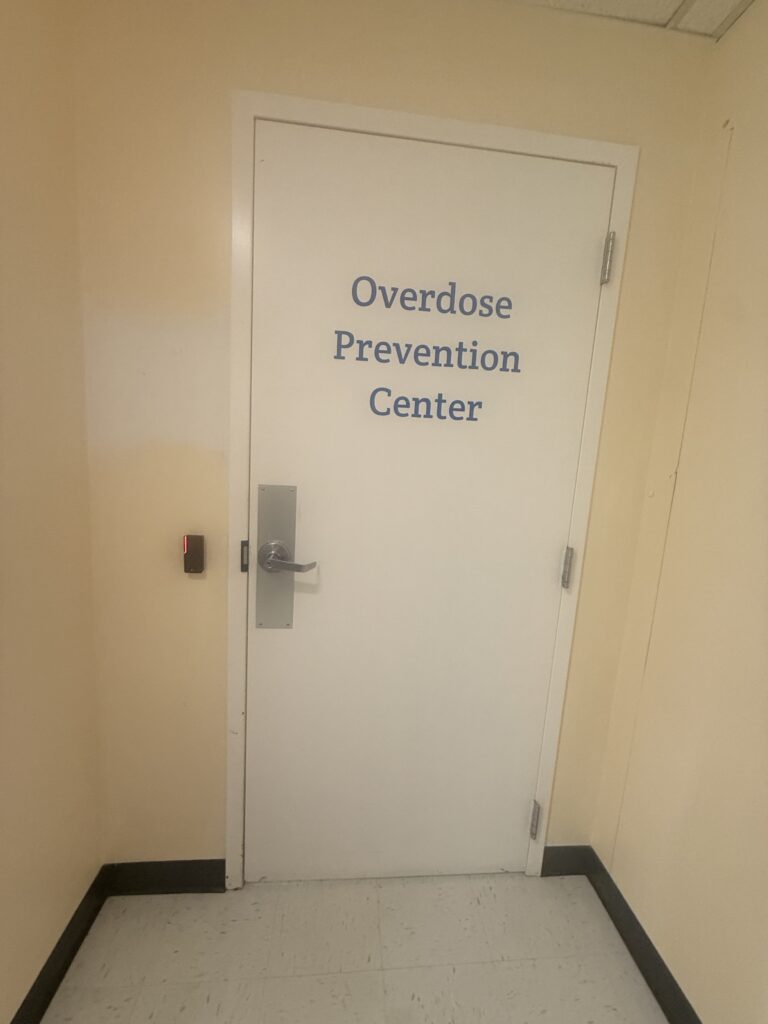

The safe use space is the smallest part of the whole operation.

The room everyone argues about is literally just one piece, almost the smallest piece, inside a much bigger ecosystem.

That building occupies two floors. It’s busy. It’s alive. It’s humming with support groups, basic needs, outreach logistics, case management, and a walk-in clinic. You can feel the difference the moment you step inside.

It’s not “come in, use, leave.”

It’s: come in, breathe, get stable, get fed, take a shower, do laundry, charge your phone, talk to someone, see the nurse, get your wound checked, get your meds figured out, join a group, take a step toward treatment if you want to… and come back tomorrow.

That is what I saw.

The part that changes people: how they treat clients

There’s a phrase they used that stuck with me: radical hospitality.

Not performative kindness. Not “customer service.”

Real, consistent human care.

They offer juice. Snacks. A warm welcome. They learn names. They learn stories. They remember what someone likes. They treat people like they belong.

Someone said it out loud: you start to know people well enough that you’re already reaching for what they’re going to ask for before they ask.

That might sound small to some readers.

It’s not small.

For folks who’ve been treated like trash in waiting rooms, judged in ERs, talked down to by systems… that kind of hospitality is not “extra.” It is the doorway.

It is the trust-builder.

And trust is the whole thing.

And I want to add something else I felt in the room, beyond the words: the calm.

Not the kind of calm where nothing is happening, this place is busy. But the kind of calm where the staff aren’t bracing for people. They’re not “managing” people. They’re with people. There’s a difference you can feel in your body when you walk in.

Overdose response that doesn’t traumatize people

They also talked about something that matters way more than people realize: how they respond when something goes wrong.

They emphasized that interventions often start early, because the monitoring is constant, and that the first-line response is frequently oxygen, not immediately blasting people with naloxone.

That matters because a lot of people avoid care for one simple reason:

They’re terrified of being thrown into withdrawal.

So when people learn, by experience and word-of-mouth, that “if something happens to me in there, I’m going to be okay”… they come back. They bring friends. They stop using alone.

And if naloxone is needed, they described using microdosed intramuscular naloxone, titrated, more precise, aimed at restoring breathing without causing unnecessary suffering whenever possible.

This isn’t chaos.

It’s calm, trained, early intervention.

And they reported that EMS calls are rare because most situations are handled on site with that early monitoring and response.

To me, that’s not just a clinical detail. It’s part of the trust architecture. It’s part of why people return. It’s part of why somebody who’s been burned by systems will take a chance on a door like this.

The clinic: “anything and everything” (and why it works)

Now let me talk about the nurse.

Because if you want the clearest picture of what this place actually is, you should picture the clinic.

The nurse described the clinic as walk-in, low-barrier care where you don’t get punished for being poor, traumatized, sick, or chaotic.

Missed appointments don’t get you kicked out.

No “three strikes and you’re out.”

People can come in saying “I’m in crisis” or “I need my inhaler” or “my meds got stolen” or “my wound is getting worse” or “I need STI testing” or “I haven’t seen a counselor in years.”

And they work with what’s in front of them.

She described medication management, holding medications for folks who are unhoused, doing blood draws and labs, wound care (including severe wounds), STI testing and treatment starts, therapy connections, bridges to primary care and psychiatry.

But what hit me wasn’t the list.

It was the way she talked about it, like nothing was beneath her. Like nothing was “not my job.”

She gave examples that don’t fit neatly into a medical chart, but they are exactly what low-barrier care means in real life. People show up in absolute survival mode. Sometimes it’s wound care. Sometimes it’s meds. Sometimes it’s, “Teresa, the bugs are on me,” and she’s helping them deal with that in a way that preserves dignity. She even mentioned cutting someone’s hair and shaving someone the other day, because sometimes the most healing thing you can offer is helping someone feel human again.

And then she said the quiet part out loud:

A lot of hospitals stigmatize our people.

So people avoid care until it becomes catastrophic.

This clinic is built to stop the spiral earlier, before sepsis, before amputation, before the ER becomes the only option left.

Wounds, blood, and the reality people don’t want to talk about

One of the questions on the tour was about big wounds. Bleeding. The realities we all see in the streets now.

Their answer was basically: yes. That happens.

And that is part of why the space is regulated, why staff are trained, why bloodborne pathogen protocols exist, and why having on-site clinical care is not a “bonus feature.” It’s essential.

Because the truth is: people don’t pause their addiction to go become medically stable first. They don’t stop being unhoused long enough to keep a wound clean. They don’t suddenly have a phone and transportation and the ability to attend three appointments in a row.

So the care has to come to where they are.

If you’ve ever seen someone trying to keep using while their body is falling apart, you already understand why.

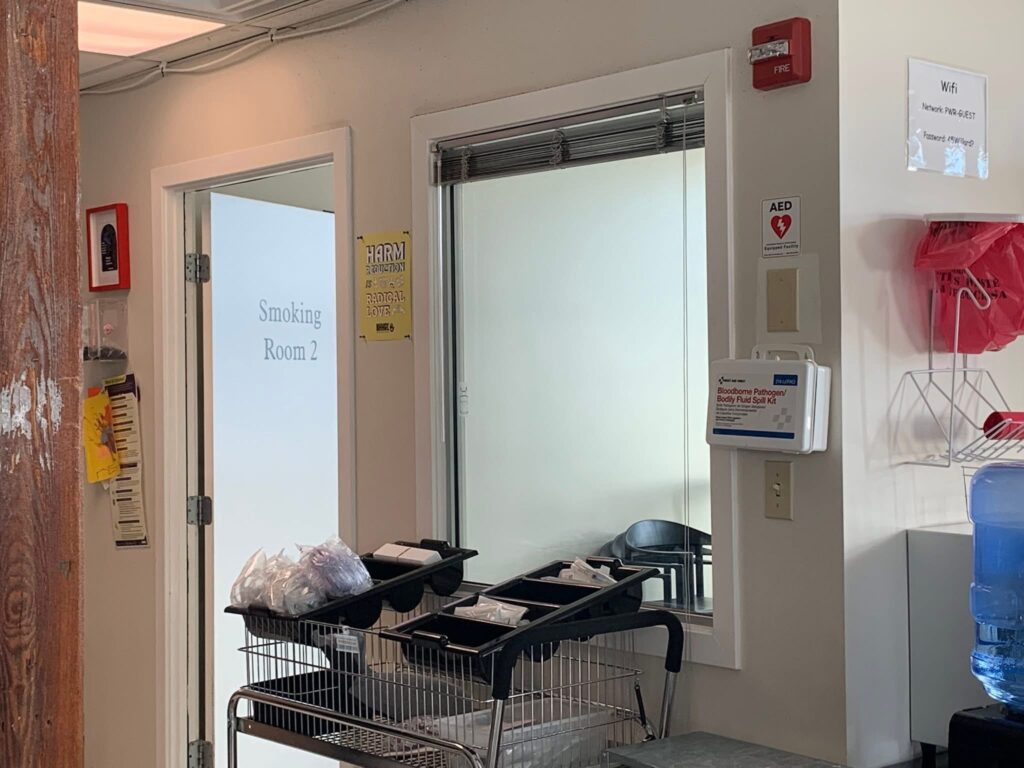

Two smoking rooms. Not one “needle room.”

This is another detail people need to sit with.

They have two rooms specifically for smoking substances. Two.

And they noted a clear pattern in route of use: the smoking space was used mostly by Black and brown participants, while the injection space was used mostly by white participants, an uneven split that reflects broader inequities in who has been pushed into which risks and which options.

I believe that translates directly to Rochester.

And it matters because if we design services around one mode of use, we will unintentionally choose who gets included and who gets left outside.

They built the smoking rooms on purpose.

Because leaving people out is not harm reduction.

A quiet lesson: not everyone can handle “busy” all the time

One of the most honest things they shared was this: the drop-in space can be lively. TVs on. People talking. Movement. Energy.

And they’ve learned they’d benefit from more quiet, low-stimulation space, a place for someone whose nervous system is fried, who’s overstimulated, who needs to come down without being in the middle of everything.

That’s not a complaint. That’s a sign they’re paying attention.

It’s what it looks like when people build services around real human beings instead of paperwork.

I’ve now visited two of the three OPCs in the United States

And I’m telling you: these centers could not possibly be further from the “shooting gallery” assumption.

They are structured.

They are service-heavy.

They are built around dignity.

They reduce death in the most direct way possible, by making it easier for people to survive long enough to accept help.

And maybe the biggest lesson I brought home is this:

People don’t walk into places that hate them.

They walk into places that know them.

That remember them.

That treat them like they’re worth the effort.

That’s what I saw. With my own eyes.

And I’m not interested in debating imaginary facilities anymore.

I left that building thinking about how many times we’ve asked people to “do better” while offering them nowhere safe to land.

This place is a landing.

And it’s saving lives.

What do you think?

Show comments / Leave a comment